Prominent Japanese artist Tabaimo focuses on the anxieties lurking beneath the surface of everyday life in her country to uncover a darker world behind the exterior of Japan’s well-ordered society. She projects her alluring, room-sized animations of typical, urban communal and private spaces—public bathhouses and restrooms, crowded trains, cramped apartment dwellings—onto complex architectural configurations that curve and tumble into space. Seemingly mundane situations unfold from these stagelike structures and morph into absurd (and sometimes grotesque) dreamlike narratives. Ordinary interiors mutate, isolated body parts perform tasks, and violence erupts, often directed sexually by men against female protagonists, although males also appear among Tabaimo’s spectrum of bodies under duress.

Tabaimo (born Ayako Tabata in Hyogo, Japan in 1975) first addressed Japan’s unique social conditions in a series of early allegorical works with the modifier “Nippon” (Japanese) in their titles—an uncomfortable designation as most Japanese avoid sensitive topics such as sexual assault, depression, or exploitation of labor.1 In works such as Nippon no Daidokoro (Japanese Kitchen, 1999) and Nippon no Yuya—Otokoyu (Japanese Bathhouse—Gents, 2000) to Nippon no Tsukin Kaisoku (Japanese Commuter Train, 2001) and Nippon no Ouchi (Japanese Interior, 2002), the adjective changed from a cheer voicing national pride to a lens through which Tabaimo considered how a generally passive culture can accommodate ostensibly contradictory and darker elements of life.

In the years that followed, Tabaimo continued her exploration of contemporary life’s puzzling nuances, though with less biting social commentary. For almost a decade, she has drawn inspiration from Shuichi Yoshida’s riveting novel Akunin (Villain),2 beginning with a group of drawings also called akunin (2006 – 2007) and followed by, among others, the video animation installations danDAN (2009), yudangami (2009), and most recently, aitaisei-josei (2015). In this body of work, she has focused on her own anxieties regarding modern life to reveal her innermost, sometimes meandering thoughts on selfhood and generations.

*****

Japanese author Shuichi Yoshida’s psychological thriller Akunin paints an ugly and depressing picture of life in modern-day Japan. The story begins with a murder and ends in a heartbreaking twist of fate. Entangled in a web of lies, deceit, and loneliness, youthful characters grapple with questions of ethics and morality as they come to terms with living in an increasingly online, virtual world. A succession of first-person narratives exposes how past events, many of them private, online affairs too personal or illicit to reveal to anyone in the real world, have shaped each character’s particular worldview, though surprisingly they all strive for the same things in life: companionship, love, and second chances. As we dive deeper into the story, we come to understand the unique and quixotic challenges of navigating between Japanese tradition and modernity.

Despite her penchant for sensational news stories and controversial subjects,3 Tabaimo was drawn neither to Yoshida’s complex, extroverted protagonists nor to the assumed villain Yuichi Shimizu, all of whom work long hours, drive fast cars, casually date online, and frequent shabby love hotels. Instead, she turned to a minor character, the quiet and reserved Miho Kaneko, the novel’s resident ingénue. The “perfectly ordinary” bathhouse girl meets Shimizu while dreaming of running a small diner. Her failed relationship with the suspected murderer and her lack of purpose exemplified Tabaimo’s interest in the attitudes of her own supposed “lost” generation, or what she calls the “crosscut” generation (danmen no sedai),4 caught between Japan’s celebrated postwar “solidarity” generation (dankai no sedai) and the younger “enlightened” generation (satori sedai).5

Born in the 1970s, members of the “lost” generation came of age as Japan was rapidly evolving into a technologically advanced society, due in part to the strong work ethic, selflessness, and group mentality of the “solidarity” generation.6 With one foot rooted in the past and the other pointed toward the future, the “lost” generation struggles to negotiate the space between tradition and modernity, isolationism and globalism, real and virtual. Yoshida’s ingénue Miho Kaneko became Tabaimo’s muse through whom she explored ideas of loneliness, narcissism, and failure that she believes characterize the lives of her contemporaries.

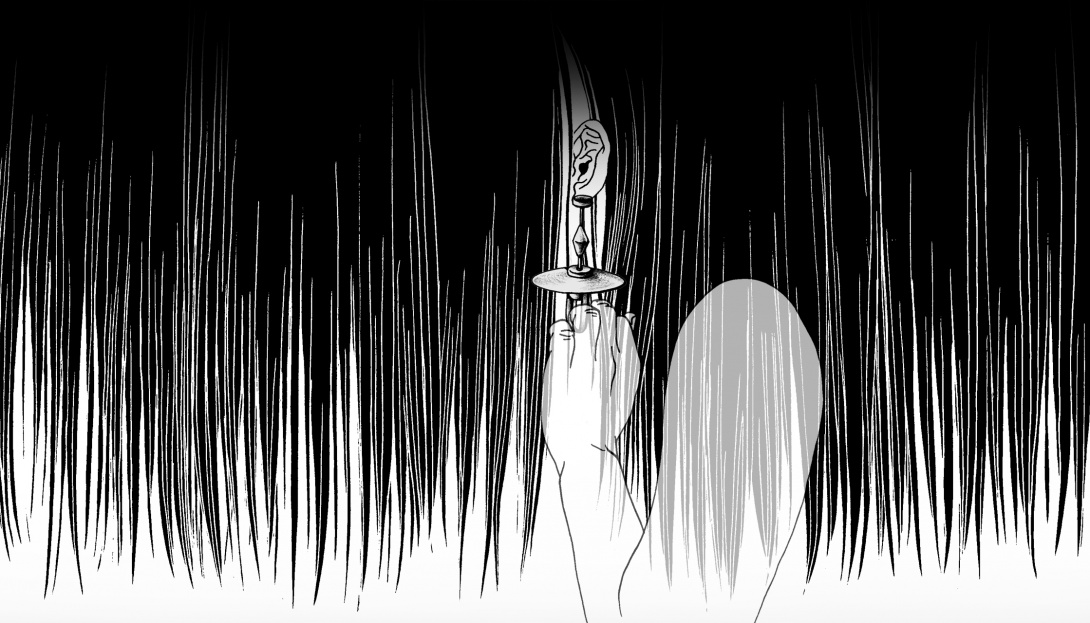

Before its publication as a book in 2007, the wildly popular Akunin appeared in 2006 as a serialized novel in Asahi Shimbun, one of Japan’s five national newspapers, accompanied by ink drawings Tabaimo produced on scroll-like Japanese paper; details of what would eventually become the akunin drawings were reproduced alongside Yoshida’s narrative. Using hair and hands as repetitive elements, Tabaimo selected words and phrases from his deliberate and careful prose to create her fragmentary images. Sequenced to match the serialized installments, the drawings likewise provide a long, continuous narrative that flows from right to left like a traditional Japanese scroll. The fluid, confident lines and otherworldly characters of Tabaimo’s signature graphic style appear like apparitions from her subconscious and provide insight into how the artist develops her eerie and spectacular video animations.

To create her richly layered animations, Tabaimo produces hundreds and sometimes thousands of drawings made with an automatic brush pen, which uses natural hair to dispel ink like a traditional Japanese calligraphy brush. Her imagery, with its muted palette, linearity, and everyday subject matter, is inspired by nineteenth-century ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) by well-known artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849). She often scans reproductions of ukiyo-e into her computer and via Photoshop lifts colors and recognizable motifs like Mount Fuji to insert into her drawings, intentionally creating a hybrid mix of past and present and blending tradition with oblique references to manga (comics) and anime (animation). She is quick to note that though she may appear to be incorporating the history of animation into her art, “the colors, textures, and designs that cover the surface of Hokusai’s prints are more important.”7

danDAN

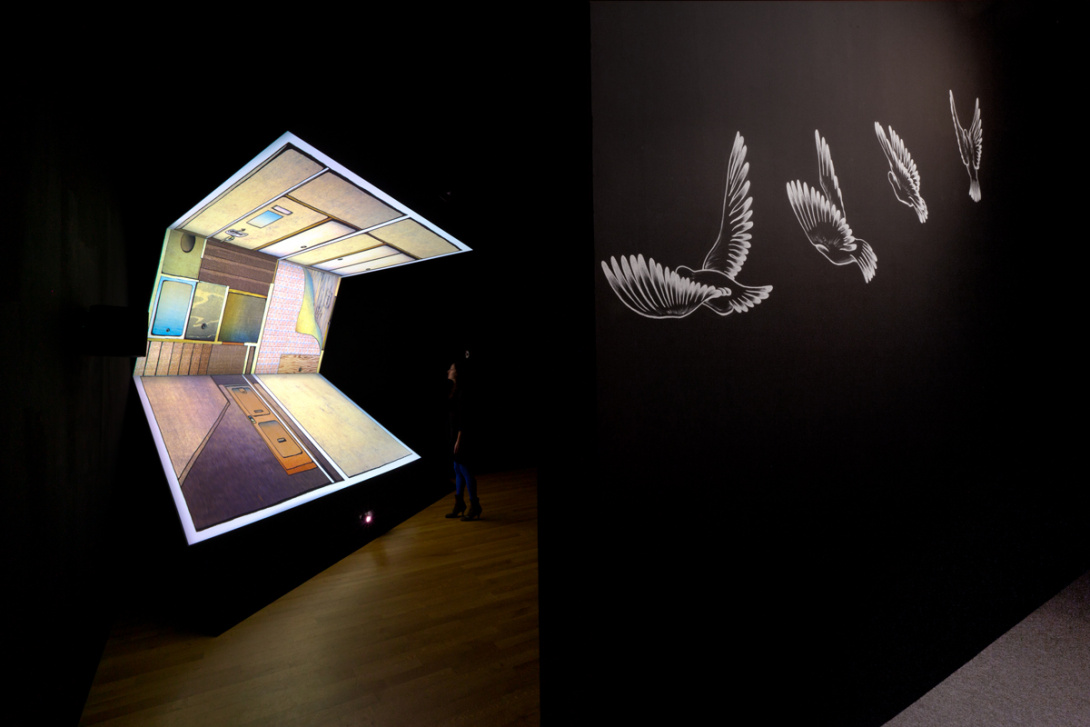

Hokusai’s colors fill the peculiar spaces of a danchi in the alluring three-channel video animation installation danDAN as Tabaimo speculated about what happens behind closed doors. Danchi were originally built as public housing for young families and today are home to employees of large corporations and young urbanites like those of Yoshida’s novel. Projected onto a three-paneled structure, Tabaimo’s cross-sectional view of a typical danchi unfurls like a hanging scroll. Glimpses into the compact units reveal behavior that ranges from mundane to disturbing: A woman takes out the trash while a man washes his face in the toilet. Another man exits the bathroom naked, walks into the kitchen, and enters the refrigerator. Biofluorescent pigeons fly through broken windows and roam empty apartments. Blood splatter covers a bed. No interaction takes place among the residents: this is a sterile and lonely place to live. As the animation moves upward and then down, our perception of the building is altered in a way that recalls the flattened perspective and asymmetry of ukiyo-e. Tabaimo further referred to ukiyo-e—“pictures of the floating world”—by plunging viewers into a shifting visual environment that is both dreamlike and nightmarish.

Additionally, Tabaimo’s presentation of danDAN recalls Hungarian-born Bauhaus experimental artist László Moholy-Nagy’s theory of the screen as a spatially constructed environment capable of embodying the experience of the modern-day metropolis. For Moholy-Nagy (1895 – 1946), the screen could play host to a number of planes offering various vistas and viewpoints.8 According to visual culture scholar Giuliana Bruno, he insisted on a screen with “multiple projections and magnification” that articulated an “array of sounds” typical of urban life.9 In Tabaimo’s danDAN, acoustical reverberations of a guitar (played by the artist) and a spine-tingling bass haunt the passageways of the danchi. Finally, the contents of the entire apartment complex disappear into an endless void—an apt metaphor for the uneasiness and instability felt by the “crosscut” generation, observed the artist’s sister and studio manager Imoimo.10 Yet, a note of hope persists: as the building disappears into darkness, a fanciful, classic arcade game tune plays, evoking the excitement of falling “into an unseen world,”11 like Alice plummeting down the rabbit hole to Wonderland.

yudangami

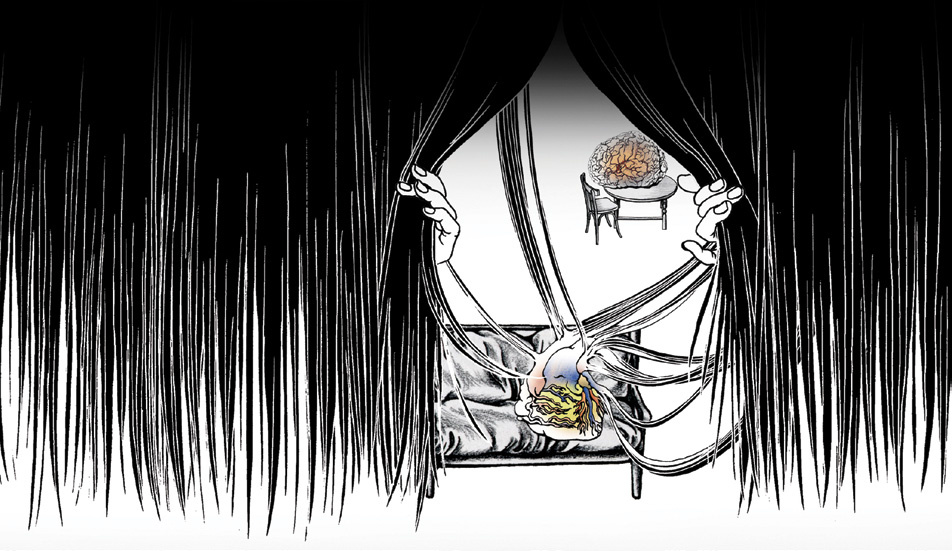

From near total darkness emerges a curtain of black hair, its fringes swaying hypnotically to cacophonous sound: arcade game tunes, mumbled chatter, electro-acoustic riffs, and the ticking of a time bomb. In yudangami, Tabaimo imagined details of Miho Kaneko’s life left out of Yoshida’s story. Reminiscent of classic Japanese horror films, disembodied hands and limbs appear from the stringy, snakelike mane, snipping and parting to reveal chilling vignettes: A lamp dangling from the lobe of a mangled ear lights a table set for two. Index fingers bathe under a shower. A heart on a couch pulsates with neon-colored blood and transforms into a beetle as a glowing brain slips off the edge of a table. Similar to danDAN, yudangami ends with the overturned contents of an apartment, caused this time by hair churning like waves in a turbulent sea.

Tabaimo conceived yudangami as a series of connected yet distinct narratives, reflecting her perception of the “crosscut” generation as individuals linked by their own self-absorption. She advanced this idea by projecting her animations onto a concave wall, enveloping her viewers in an artificial world and fabricating a hallucinatory state of mind. The approach recalls late nineteenth-century Western visual technologies such as the cosmorama and moving scenic panorama (both precursors to early cinema), which immersed audiences in near 360-degree environments of historical scenes, famous places, and exotic landscapes. As Bruno observed, these spaces of public spectatorship altered perceptions of time and place through architectural forms of display: curved screens, moving walls, magic lantern shows and phantasmagorias, cabinets of curiosity, the camera obscura, vitrine and window displays, dioramic shows, and tableaux vivants.12 Turn-of-the-century audiences reacted with awe and amazement as the real and virtual collapsed before their eyes.

Today’s global audiences are accustomed to multisensory devices and screens displaying interactive 3D simulated realities. The virtual is no longer terrifying, but part of everyday life, often exceeding actual lived experience. Nowhere is this more true than in urban Japan, where media and technology overwhelm the senses. Yet, cultural traditions remain woven into the fabric of everyday life, while tradition and modernity can be at odds.

aitaisei-josei

In aitaisei-josei, Tabaimo considered how conflict between social obligation (tradition) and personal desire (modernity) can lead to unwelcome and dangerous results. Coined by the artist, aitaisei-josei translates as “the relativity of two women” and was inspired by the mistranslation of the “theory of relativity” (sotai) during the Taisho period (1912 – 26) as “the relationship between a man and a woman” (aitai). Because aitai can also mean a “double suicide,” the theory of relativity became bemusingly associated with this fatal act.

Tabaimo’s outlandish narrative connects the troubled affair between Miho Kaneko and Yuichi Shimizu with that of the beautiful courtesan Ohatsu and the young merchant Tokubei from Sonezaki Shinju (The Love Suicides at Sonezaki), a famous eighteenth-century bunraku (puppet theater) play written by Monzaemon Chikamatsu (1653 – 1752). In Kaneko’s apartment, a sofa personifies Ohatsu and Kaneko and a table embodies the spirits of Tokubei and Shimizu. As Kaneko’s apparition shuffles around the interior space, her activities trigger bizarre events and bring inanimate objects to life: A hanging lamp morphs into a full moon that transforms into a well in the floor. A bottle exhales a plume of smoke. A tree emerges from behind the apartment and unleashes a violent lock of hair. Eventually, a viscous white substance fills the apartment and wipes away its contents.

Tabaimo’s use of props (a sofa arm and table leg) and stage design elements (translucent plastic and paint) extend the visual field of her projections into the space of spectatorship, creating a hyperreal environment that takes on a physical as well as virtual dimension. This is symptomatic of a “new spatial order,” noted art historian David Joselit, “in which the virtual and the physical are absolutely coextensive, allowing a person to travel in one direction through sound or image while proceeding elsewhere physically.”13 In the video animation, the table twists, bends, and stretches, rubbing itself against the sofa—a metaphor for young love. The literal translation of aitai is “I want to meet”; it is often used as an expression of longing, as in “I miss you.” Tabaimo’s sofa and table “meet” in virtual space like many young adults who browse online in search of friendship and love.

*****

The world we inhabit today is essentially different from anything we have known. The pace, extent, and very nature of change present fundamentally new challenges. As technological advances are made, connections with the past are lost; miscommunication between generations increases; the world becomes an abstracted reality. And yet, opportunities are boundless as pathways are opened to unimagined possibilities. In Japan, where reverence for the past directly abuts an uncharted future, the turmoil is intense. One result is anxiety—the ground itself seems shaky as everything is in continual transition. Tabaimo imagines a world where social constraints are loosened and traditional boundaries expanded—a fantastical “floating world” where one is free to drift endlessly without regret.

Rory Padeken

Assistant Curator

Notes

1. Yuka Uematsu, “Tabaimo: Outside-In,” in Tabaimo: Danmen (Kyoto: Seigensha Art Publishing, 2009), 107.

2. Shuichi Yoshida, Villain, trans. Philip Gabriel (New York: Vintage Books, 2010). Originally published as Akunin (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2007).

3. Rachel Kent, “Unique Waters: Tabaimo’s Immersive Art,” in Tabaimo: Mekurumeku, ed. Rachel Kent (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2014), 15.

4. Tabaimo, “DANMEN,” in Tabaimo: Danmen, 3.

5. Roland Kelts, “The Satori Generation,” Adbusters, last modified: May 7, 2014, https://www.adbusters.org/article/the-satori-generation/.

6. Ashley Rawlings, “All That Creeps Beneath the Surface: Tabaimo,” artasiapacific, November/December 2010, http://images.jamescohan.com/www_jamescohan_com/1d60201f.pdf.

7. Kent, 13.

8. Giuliana Bruno, Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 112.

9. Ibid., 113.

10. Imoimo quoted in Rawlings.

11. Ibid.

12. Bruno, 152.

13. David Joselit, “Navigating the new territory: art, avatars, and the contemporary mediascape,” Artforum, June 2005, 276.