–

The Collector’s Perspective

Interview with Michael Wornick, by Susan Krane, Oshman Executive Director, San Jose Museum of Art, October 24, 2014, at the San Jose Museum of Art.

Since 1991, Michael Wornick has been the managing partner at Wornick Associates. After working in real estate finance and development for over a decade, he undertook graduate studies in art history and received his MA from Dominican University of California, San Rafael, in 1996. He served on the boards of trustees of The Mexican Museum, San Francisco, and Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California, from 1995 – 98.

| SK: | What inspired you to collect—and then seriously study—Mexican modernism? |

| MW: | In the early 1990s, Latin American art just didn't have a broad audience. Although work had been exhibited often in New York in the 1920s and 1930s, and in Texas in the 1950s and 1960s, at that time it seemed to me that the mania for Frida Kahlo overshadowed the work of the muralists. |

| SK: | Had you also traveled to Mexico by that time? |

| MW: | Mexico first came into my life in 1968, when I was nine years old. My favorite uncle had a jewelry business and imported silver from Mexico. He was there for the summer Olympics in Mexico City in 1968 and he brought home for me some beautiful drawings on handmade amate paper (made from tree bark). |

| I was also influenced by my parent's knowledge of art. They came to collecting later in life, but their crowd of artists and faculty, and their visits to artists' studios, gave me an interesting viewpoint. They collect art in all media, including work by Bay Area figurative artists. | |

| SK: | Did you begin collecting seriously in parallel with your studies in graduate school, and your research for your thesis on Diego Rivera? |

| MW: | I started collecting before graduate school. The first gallery I went to was Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art in New York. Unbeknown to me then, there was a gallerist in San Francisco, Marvin Moss, who also specialized in Latin American art. As I became interested in the artists he represented, I learned more about Mexican art and it led me to go to graduate school. |

| SK: | Your collection today is focused very specifically on José Clemente Orozco's figure studies and you've deaccessioned works by other artists along the way. How did the collection evolve? |

| MW: | Your question reminds me of something I had forgotten. As an undergraduate, I studied real estate finance and development, but I also took an art appreciation class with a very interesting professor. For one of the final exams, he projected an image onto a screen and required us to name the artist, the period, the medium, the influences, the school—for example, Expressionism, Surrealism. I remember how much fun it was compared to everything else I was doing—economics, real estate, math—everything. |

| Art started making sense to me then; deciding to collect and what to collect came later. As I walked through museums, I found myself not so interested in landscapes or still lifes. In fact, the more I looked at museums in Paris, London, Mexico, New York—wherever I was traveling for work or for pleasure—all my favorite images were of the human figure and particularly of the female figure: Modigliani, Picasso, El Greco. In Mexico, you had such a strong patriarchal overtone that women were not so frequently depicted in art (except for religious iconography) until the muralists. | |

| The Mexican Revolution in 1910 brought a sea change. In 1921, Mexico's new minister of public education, José Vasconcelos, said, "It's time to create a national Mexican identity, different from the one that we have. And the way that we're going to do that is to create a public art." That decision set Mexican modernism onto its trajectory. | |

| SK: | Was this the pivot point on which you wanted to focus when you started collecting? |

| MW: | In graduate school, my thesis topic was "Sacred, Sensual, and Sublime: A Diverse Iconography of the Murals and Frescoes of Diego Rivera, from 1922 to 1938." I looked at his murals and tried to decipher how he used women as generalized symbols to depict fertility, fecundity, and allegories of rebirth. |

| SK: | He was the introvert among other more muscular, flamboyant personalities. |

| MW: | Rivera and Kahlo were the "it" couple. Orozco just set about doing his work in a quiet way, sometimes grim and sober. |

| SK: | And so, did his personality prompt your focus on his work? |

| MW: | I started with the human figure, especially the female figure, in twentieth-century Latin American art. I was trying to acquire a work by each of the pivotal artists. My budget was constrained and I realized that I was never going to acquire a Frida Kahlo, or a great Rufino Tamayo, or a great Wifredo Lam, or a great Joaquín Torres García. |

| I made a conscious decision to rethink everything. I took all the artwork out of my house and put it in storage. That's what brought me back to Orozco. Like many collectors, I began by buying the prints. | |

| The first drawings I bought at auction were not attributed. In fact, they were framed in such a way that you couldn't see the date or the signature. But I recognized them immediately as his work and only later discovered they were mural studies for Prometheus, at Claremont College. | |

| You couldn't find an Orozco work for sale in the States, except maybe once every four or five years. I started buying Orozco's figure drawings aggressively only in the last ten years. |

|

| SK: | In preparation for his murals, Orozco made the gestural, very direct figure sketches that you have in your collection, yet he also did fleshed-out studies in gouache and mixed media, as well as studies for his compositions and for the narrative cycles within the murals. His murals are complicated and working in fresco is unforgiving. You can't make a mistake. Do you think there are legions of studies that haven't been located or that many of his studies just didn't survive? |

| MW: | Everything happened to these drawings. I think some of them probably got spread out as a tablecloth when they would eat a meal during their ten hours of labor up on scaffolding. If you look at some of the drawings in my collection, they've been folded up like origami. At that moment, they obviously were not prized as works of art. Others have a certain type of paint splatter, which I now know signifies that the drawing is the final version of the preparatory sketch. |

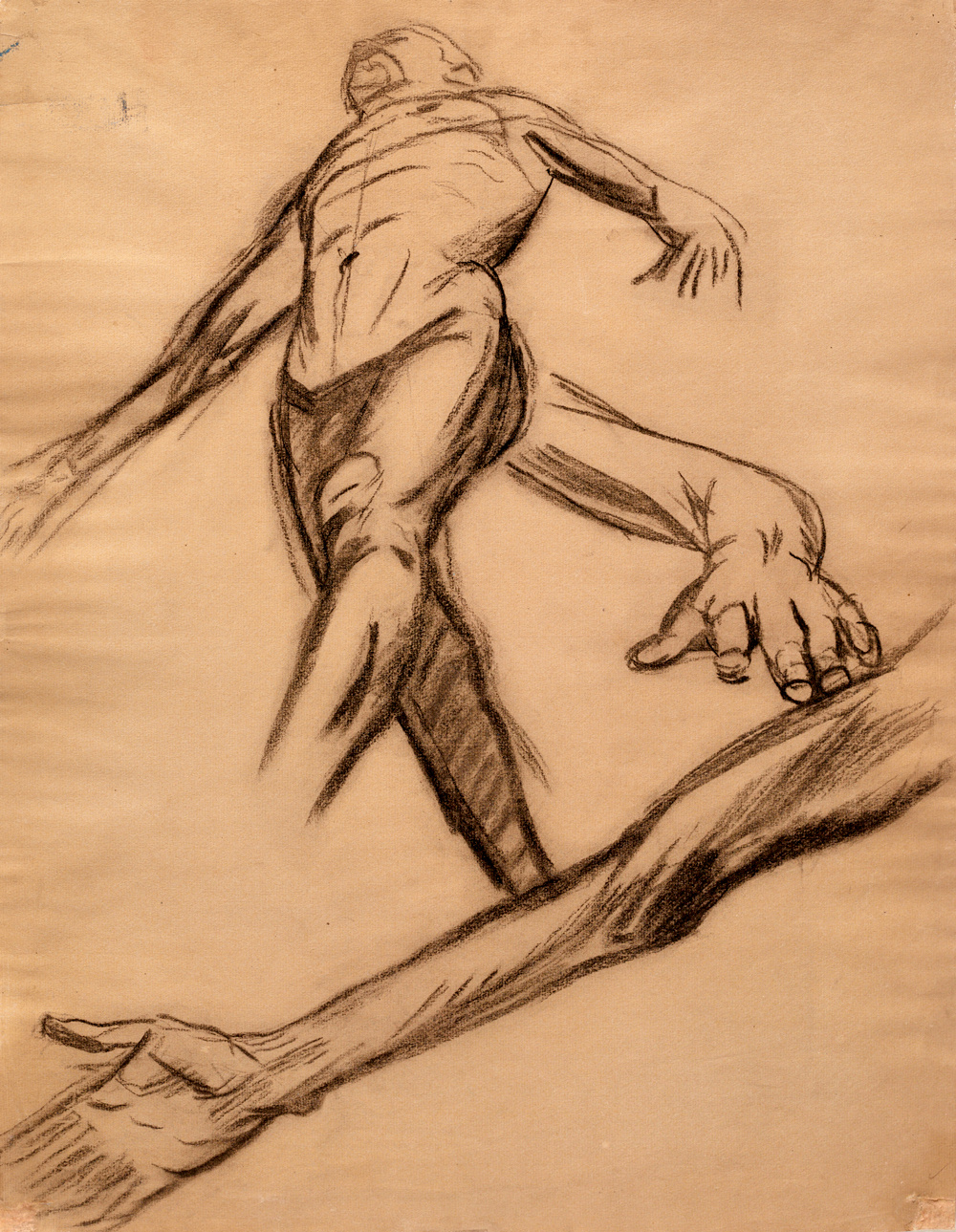

| SK: | Why did you decide to focus just on the single figure studies—not the multifigure studies, not the compositional studies, not the painterly studies, but the immediate, very intimate studies of hands and arms and dynamic poses, often done from the live model? |

| MW: | That's a good question and I think the answer is twofold. One, I reacted viscerally to the power of the line that Orozco created. To paraphrase, Orozco said, "It's amazing what you can do with a pencil and a piece of paper." He was a phenomenal draftsperson. Simply with chalk or ink or Conté crayon, he could create muscle, tendon, tissue, movement, shading, chiaroscuro. It seems effortless. I also thought the figure drawings should be plentiful. |

| SK: | There is something very timeless about these drawings. Some feel more classical or academic; some feel much more Cubist. |

| MW: | We know that Orozco was trained as an engineer and had some architecture training. Even in these early studies, he was trying to work out what happens architecturally on the wall, how to work with a stairway or a dome, as well as to work out how the narrative speaks. I do think that these figures (even though some are, anatomically, just an arm) relate to the architectural spaces and the narratives. |

| SK: | In addition to the fact that Orozco was Rivera's rival and the underdog, did his radical politics and his interest in the human drama of oppression appeal to you? Were you engaged particularly by his tragic—idealistic and yet tragic—take on history and on the modern world? |

| MW: | Orozco is such a complex figure. His funeral (he's buried in the Panteón Civil de Dólores in Mexico City) was attended by a number of important dignitaries, among them Octavio Paz. I believe it was Paz who said, "Orozco never smiled in his life." He was often characterized as a humorless man. |

| But we have to think about the man as a part of history. Let's think about what we know about him. As a young man, he was working with gunpowder and in an accident lost much of his left hand. He became a one-armed artist. And a muralist. Imagine being up on a scaffold with one arm. He also lived through the revolution and saw the carnage of war, carts full of bodies, disfigured corpses. And he did caricatures for a newspaper: he depicted people's everyday life in the barrios. The subjects of his very early drawings and watercolors were women who were prostitutes and men who were past their prime: he called the series the "House of Tears." | |

| SK: | Those were the drawings from his portfolio that were confiscated at the border in Texas when Orozco first came to the United States in 1917. |

| MW: | Yes. He then ended up working as a sign painter, for a while, in San Francisco. Orozco was a guy who faced many obstacles. Artistically, he was influenced by the humanism of Goya, El Greco, Grünewald, and Giotto. |

| SK: | He lived through the Mexican Revolution and the Great Depression and through two world wars. How do you think the turmoil of his times influenced his vision and his politics, his stridency? |

| MW: | He felt an affinity for the masses. We also know that he was vehemently anti-political, anti-clerical, anti-military, anti-organization, and anti-establishment. He was opposed to everything organizational because he felt organizations were corrupt: the church, the state, the military, the police. He saw them as betraying their values and their doctrines. This led to his work as an artist for La Vanguardia (The Vanguard), a revolutionary paper edited by Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo), one of his teachers at the Academia de San Carlos (Academy of San Carlos). But over time he distanced himself from the left-leaning artists. |

| SK: | You've developed a relationship with the artist's family over the years. |

| MW: | Yes, after I bought one of Orozco's illustrations for John Steinbeck's The Pearl (La Perla), 1947. Five of the drawings made it into the book; the sixth did not—and that's the one I was able to purchase. It came from the estate of the artist. |

| It established me as a serious collector in the eyes of the family and I had an introduction to the grandson, José Clemente Orozco Farías. He came to visit, saw the Orozco works in my collection, and went back and told his father, "There's this kid in San Francisco collecting your father and my grandfather's work." | |

| SK: | Have many of Orozco's drawings stayed with the family? |

| MW: | Early in Orozco's career, a doctor in Mexico City, Dr. Carrillo Gil, had access to the greatest of Orozco's works (now in the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil in Mexico City). He was there on the scene in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. In my judgment, he bought some of Orozco's best works—not many of the preparatory sketches but many complete drawings and studies for the murals and paintings. Sometimes, the sketches and preparatory works for murals at government buildings and universities stayed with those institutions. Those that did not often remained in the family. |

| Early on, to locate and learn more about the drawings, I purchased a copy of every catalogue for every Latin American sale at Christie's and Sotheby's for the past twenty-five years. Then I went online and found every Orozco exhibition that was mentioned and I contacted those galleries and museums for checklists. I gathered images from books. And so I built a database of Orozco drawings for my reference. | |

| SK: | There are two things you've talked about that are especially intriguing and perhaps may seem contradictory: Orozco's inability to connect one-on-one with people and, on the other hand, his intense connection with the human struggle, through mythologizing and universalizing that struggle. |

| MW: | To my mind, Orozco is something of a paradox. If you read the letters that he wrote home to his wife, Margarita, when he was in New York or San Francisco or Texas, or if you read his letters to Jean Charlot (one of his fellow muralists, who had moved to Hawaii), you find in Orozco an actual tenderness. This is a guy who's trying to make work, sell prints, raise money to send home to his family. This is a man who takes his responsibilities seriously. |

| If you contrast Orozco's work with that of the other muralists, like Rivera, his women are not allegories or caricatures. Look at Orozco's portraits of his mother and his grandmother: they are powerful. You feel the personality. He wasn't glorifying them. He showed them as stern figures, or with dignity. He revealed their nature. The figures in his murals are, I think, as good as anything done during the Italian Renaissance. |