Figure Drawings from a Fiery Genius

José Clemente Orozco’s Studies

in the Michael Wornick Collection

—Ruben C. Cordova, PhD, art historian and curator

Drawings provide the most direct access to José Clemente Orozco’s fiery genius, precisely because drawing was the crucible in which his visionary art was created and refined. Unlike his contemporaries, Orozco deeply valued his rigorous training at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (National School of Fine Arts) in Mexico City, where Antonio Fabrés had students draw the same model in the same pose for weeks or months at a time. Orozco’s instructor Gerardo Murillo (a.k.a. Dr. Atl), by contrast, even as a student, emphasized the liberties taken by great artists: Michelangelo did not merely replicate muscles, but made them “bulge or sink rhythmically as a poet manipulates sound . . . form was made flesh on the ceiling of the Sistine because of an ideal that strove to be born rather than a mirror held to bodies born of women.”1

Orozco learned spontaneity by drawing models in momentary poses, as well as in motion. Prodigiously varied drawings served as his artistic bedrock: they permitted Orozco to endow his tragic themes with a powerful terribilità, which is evident in the studies for major murals under discussion here.

Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (National Preparatory School), Mexico City, 1923 – 27

The Escuela Nacional Preparatoria served as the laboratory for the initial phase of Mexican Muralism, which was inaugurated by José Vasconcelos, who was the Secretary of Public Education (SEP) from 1921 to 1924. Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Orozco, who later became known as the “big three” of Mexican Muralism, all painted their first murals at the preparatory school. Orozco had the largest program, which included portions of three floors and the courtyard’s central staircase.2 The compositional study for Indian and Teocalli, 1926, in the staircase is an outstanding example of how Orozco used harmonious geometric structures to govern the disposition of his human forms. Girders of triangles and parallelograms demonstrate his fluency with the Golden Section.3 When he painted the fresco, Orozco changed the orientation of the top figure’s left arm, extending it forward, based on the drawing Study of arms and torso.

Orozco stitched together elements from his careful anatomical drawings, such as the Study for right arm, which he used for the standing figure with the knife in the Cleveland Museum’s Study for Ancient Races, 1926.4 He deployed these preliminary drawings in many ways. Though the model is viewed from behind in Study of arms and torso, Orozco appears to have used the arm and hands for the figure lying on his back in the Cleveland drawing.

Peasant with hands clasped marks a pivotal political transformation. Orozco’s first version of Revolutionary Trinity, 1923 – 24, was a positive view of the Mexican Revolution, consistent with the hammers, sickles, and red stars that he painted on the arches on the first floor.5 In his first iteration of the mural, this figure was an engineer. In the second version, painted in 1924, Orozco transformed him into a grieving, fearful peasant and he changed a worker with tools into a handless, despairing peasant. This caustic, tragic world-view pervaded Orozco’s work for the duration of his life.

Pomona College, Claremont, California, 1930

In the mural Prometheus, for Pomona College, Orozco depicted the Titan who stole fire from the gods and gave it to humans, for which he was punished with eternal torment. David W. Scott emphasized the mural’s landmark status as “the first major ‘modern’ fresco” in the United States. In contrast to the bland and “decorous” murals that had preceded it, Prometheus was expressionism writ on “a monumental scale.”6

Orozco began by making general compositional studies, the second of which has a centrally posed Prometheus who corresponds roughly to the figure in the finished mural.7 Paintings by Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez (1824 – 1904) and El Greco (1541 – 1614) have been posited as sources for the Prometheus figure, whose pose with one leg kneeling and one leg extended is unusual. I would add to these possible sources the work of William Blake (1757 – 1827) and other paintings by El Greco.8 Orozco was deeply immersed in the writings and artworks of Blake and El Greco was one of his favorite artists.

Orozco made the three drawings for Prometheus in the Wornick collection at an early stage of research for this mural, which is why they are more naturalistic and more specific than most of the extant studies. The pose in Untitled (1) is much like that of the central figure in Prometheus, but the model is not observed from a directly frontal position and his left hand is not over his head. Orozco must have intended this study for a subsidiary figure recoiling from or consumed by the flames, like the figure behind Prometheus’s right hip in the mural.9 Similar hand-shading-the-face poses permeate El Greco’s religious paintings, where figures commonly have to shield themselves from blinding, supernatural light. Untitled (2) is also a variation on Prometheus’s pose, and it is also viewed from left of center. This figure most resembles the man in the right foreground of the mural, who is facing the other direction. At least three other drawings mark the development of the 180-degree rotation of this figure.10 The study of hands in the Wornick collection also exhibits a higher degree of naturalism than the stylized, expressionistic hands in the mural, which reach to the sky in a frenzied manner much indebted to El Greco’s striving, ecstatic figures. After he completed this mural, raging firestorms became almost the default background of Orozco’s murals; in their nonspecificity, they recall El Greco’s habitual ambiguous melding of sky, clouds, and earth.

Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, 1932 – 34

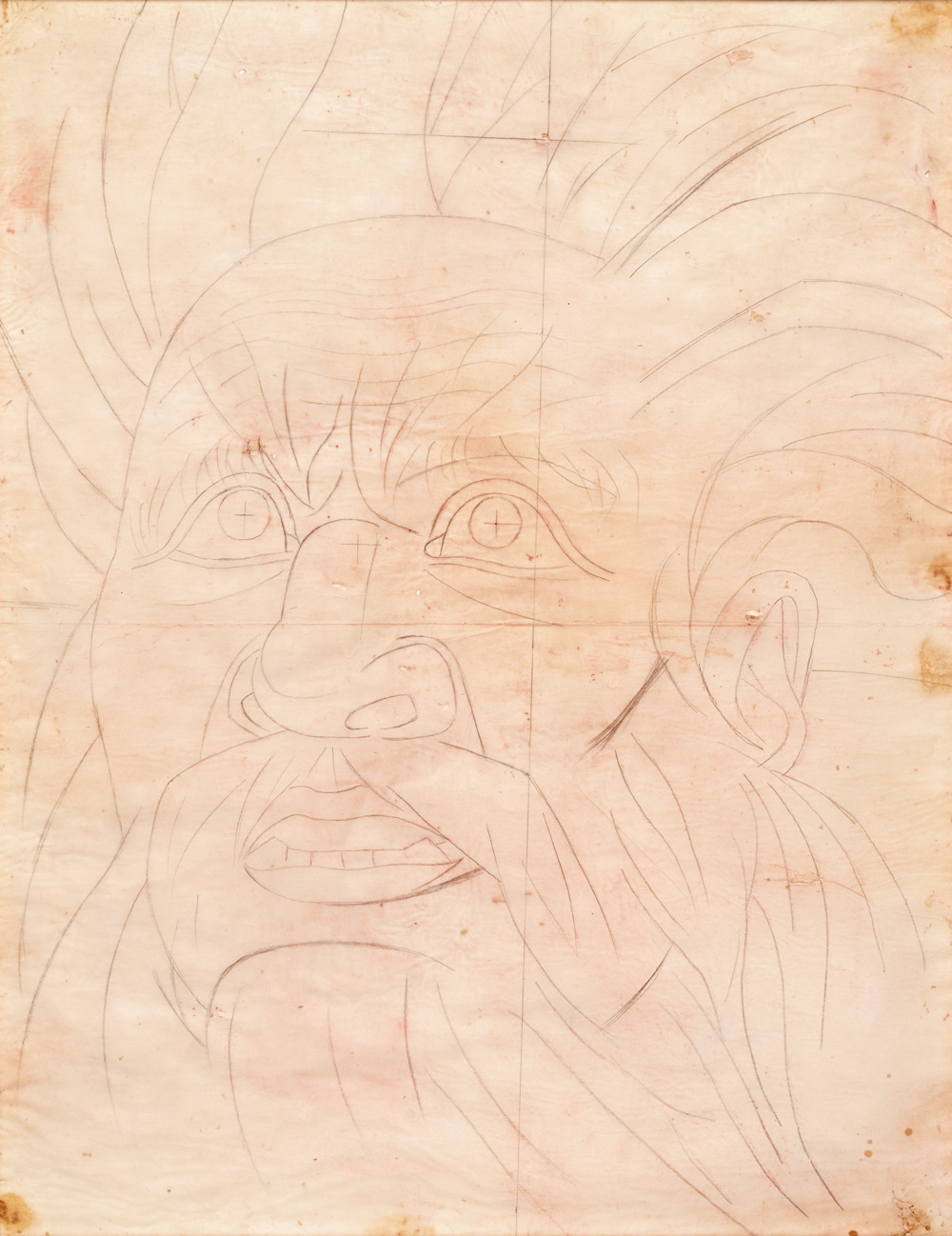

The Epic of American Civilization, Orozco’s massive mural program in the library at Dartmouth College, likely owes a structural debt to William Blake. Jacquelynn Baas related several of Orozco’s narrative panels to Blake’s illustrated books America: A Prophecy, 1793 and Europe: A Prophecy, 1794, including The Departure of Quetzalcoatl, which is represented in the Wornick collection by a working drawing for Quetzalcoatl’s head.11 This wrathful Quetzalcoatl, who could pass for any angry Old Testament prophet, is perhaps Orozco’s most Blake-ean figure. Compare, for example, Satan in the watercolor version of Job’s Evil Dream, tempered by stylized facial features that recall those in the first true fresco of the Mexican Mural renaissance, Jean Charlot’s Massacre in the Templo Mayor of 1922 – 23. The drawing in the Wornick collection is squared (marked with perpendicular lines) to facilitate transfer of the design to the wall or to another drawing, such as the similar head of Quetzalcoatl in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. In his mural at Dartmouth, Orozco depicted Quetzalcoatl being driven into exile by angry compatriots who, according to some traditions, wanted to revive the practice of human sacrifice. Quetzalcoatl vowed to return and exact revenge in the year Ce Acatl, which corresponds to 1519, the year Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico, which is why Cortés is sometimes viewed as the second coming of Quetzalcoatl.

Orozco deployed his study of the arm and clenched hand for a vital detail in the mural: the very hand with which a masked priest excises the heart of a still-living victim in the panel Ancient Human Sacrifice, 1932 – 34, which is also at Dartmouth.12

Hospicio Cabañas (Cabañas Cultural Institute), Guadalajara, Mexico, 1937 – 39

A frescoed dome at the Hospicio Cabañas is the physical and symbolic summit of a stupendous mural cycle that is nothing less than the culminating synthesis of Orozco’s artistic career. A man in flames ascends the center of the dome, surrounded by gray reclining figures that represent the other elements—earth, air, and water. In the study in the Wornick collection, Orozco refined the relationships among the various forms. If, in this drawing, the central figure seems to walk on the elongated arm as though it were a plank, in the fresco Orozco gave the various limbs a circular orientation, echoing and amplifying the shape of the dome that encloses them. The large left hand in the drawing assisted in Orozco’s rendition of the oversized hands and feet in the fresco, which essentially become expressive torches.

Thematically, the Christs who destroyed their crosses, the Prometheuses who snatched fire from the skies, the Icaruses who dared to fly too close to the sun, the Hidalgos who sparked revolution, and the conquered and conquering Quetzalcoatl/Cortéses find their final apotheosis in Orozco’s flaming man. Philosophically, it’s a Blake-ean/Neitzschean confounding of the iconographies of good and evil, of heaven and hell. The drawings discussed here provide illuminating access into Orozco’s creative process during critical junctures of his mural career.

1 Jean Charlot, The Mexican Mural Renaissance: 1920 – 1925 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963), 227.

2 I use the title as it appears in José Clemente Orozco and Jean Charlot, The Artist in New York: Letters to Jean Charlot and Unpublished Writings, 1925 – 29 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1974), ill., unpag.

3 Some scholars assume Orozco lagged behind Rivera and Siqueiros in this regard, but Charlot pointed out that, “On his first day on the job, Orozco handled more often the square and the ruler than the brush, patiently incorporating into his work the architectural modules of the surrounding columns and arches. . . . So precise was his planning that even the width and length of nose and eyes were established through mathematical computations.” Jean Charlot, online posting of cuts made to the manuscript for The Mexican Mural Renaissance, 229/370.

4 Orozco omitted the knife in the fresco. See Orozco and Charlot.

5 For a discussion of Orozco’s participation in the artists’ union that produced a manifesto positing a revolutionary trinity comprising soldier, peasant, and worker, see Alicia Azuela, “Graphics of the Mexican Left, 1924 – 1938,” in Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, ed., Art and Journals on the Political Front, 1910 – 1940 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997), 247 – 68; Charlot, The Mexican Mural Renaissance, 241 – 51.

Though several scholars have recently dated the second version of Revolutionary Trinity to 1926, Charlot, who was present when it was painted, dated it to 1924. He reproduced tracings (ills. 21a and 21b) and photographs (plates 37a and 37b) of both states of the mural. See Charlot, The Mexican Mural Renaissance.

The Fogg Museum at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts owns a drawing of the man with clasped hands that was done before the drawing in the Wornick collection because it is frontal in orientation and more naturalistic. The muralist’s son Clemente V. Orozco owns a compositional drawing for the second version of Revolutionary Trinity that he dates 1923 – 24, in which the figure with the clasped hands is monumentalized and tilted toward the left, as in the drawing in the Wornick collection. The drawing has linear framing devices on all four edges. Though Orozco could have made it in New York as a study for a lithograph he executed in New York in 1929 (he had photos of his murals sent to him there so that he could extract figures for this very purpose), he often placed framing devices on the sides of his mural studies. The lithograph corresponds very precisely to the drawing in the Wornick collection. For illustrations of the lithograph and the two drawings, see Clemente V. Orozco, José Clemente Orozco: Graphic Works (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 28 – 29.

6 David W. Scott, “Orozco’s Prometheus: Summation, Transition, Innovation,” in Marjorie L. Harth, ed., José Clemente Orozco: Prometheus (Pomona, California: Pomona College Museum of Art, 2001), 13 (reprinted from the College Art Journal 17, 1 [1957]). This catalogue also has the best reproductions of the mural and the related studies.

7 For the recollections of Thomas Beggs and Crespo de la Serna, and illustrations of the now-lost second compositional study (as it appeared in the Claremont College student newspaper) as well as the final general compositional study, see Laurance P. Hurlburt, The Mexican Muralists in the United States (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989), 34 – 36.

8 Lisa Mintz Messinger connected the unusual pose of Prometheus’s legs to El Greco’s St. Sebastian in “Pollock Studies the Mexican Muralists and the Surrealists: Sketchbook III,” in Katharine Baetjar, ed., Jackson Pollock Sketchbooks in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997), 63. Such eccentric poses are in fact an El Greco trademark. This combination is replicated in El Greco’s Baptism, 1597 – 1600, in the Museo del Prado, Madrid; it is rendered upside-down by a figure lying on his back in his Resurrection, 1597 – 1600, also in the Prado; and it is rendered ambiguously in the large draped figure in his Vision of St. John, 1609 – 14, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. El Greco also used this pose in his unfinished St. Jerome, ca. 1610/14, in the National Gallery, Washington, DC. Justino Fernández pointed out precedents in Michelangelo’s St. Andrew figure in the Last Judgment, 1535 – 41, in the Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Vatican City; Tintoretto’s St. Sebastian, 1579 – 81, in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice; and El Greco’s St. Sebastian, 1580, in the Museo catedralicio, Catedral de San Antolin de Palencia (Cathedral of Palencia), Spain. See Justino Fernández, Orozco: Forma e Idea (Mexico: Editorial Porrúa, 1956), 55.

Karen Cordero Reiman noted the similarities between Prometheus’s legs and the main figure in the Mexican academic artist Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez’s Fall of the Rebel Angels of 1850; see “Prometheus Unraveled: Readings of and from the Body: Orozco’s Pomona College Mural (1930),” in Renato González Mello and Diane Miliotes, eds., José Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927 – 1934 (Hanover, New Hampshire: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College in association with W. W. Norton & Co., New York, 2002), 114. Reiman ingeniously noted that the flames behind Orozco’s Prometheus suggest the fallen angel’s batlike wings, “while at the same time evoking a divine fire that punishes and purifies, consumes and gives life.”

William Blake rendered several figures with a bent knee and extended leg that could have inspired Orozco, including Satan in Job’s Sons and Daughters Overwhelmed by Satan and Satan Going Forth from the Presence of the Lord, rendered in watercolor in 1805 – 1806 and again in 1821, and as published as engravings in 1826. His tempera version of Satan Smiting Job with Boils (ca. 1826 – 27) features a Satan with red, batlike wings. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Blake's_Illustrations_of_the_Book_of_Job#.

Orozco became immersed in William Blake’s work at the apartment of Orozco’s New York agent and companion Alma Reed known as the “Ashram.” Emily Hamblin, who frequented Reed’s salons and who wrote three books on Blake, even gave a lecture comparing Orozco and Blake at one of Orozco’s exhibitions. González Mello believes exposure to Blake decisively impacted Orozco. See Renato González Mello, “Orozco in the United States: An Essay on the History of Ideas,” in González Mello and Miliotes, 42 – 43.

9 In the final general compositional study, the face of Orozco’s figure is largely obscured, though only the top of the head is blocked by the figure’s forearm in the finished mural. See Harth, 90, 28.

10 These drawings are in the collection of Pomona College. See ibid., 96, 102, 104.

11 See Jacquelynn Baas, “The Epic of American Civilization: The Mural at Dartmouth College (1932 – 34),” in González Mello and Miliotes, 168.

12 The cult statue of the Aztec patron god Huitzilopochtli presides over this sacrifice. He wears serpentine ornaments bearing human hearts and he holds a shield and darts in his left hand. Baas, 350 – 51, n. 69, misinterpreted this statue as a “disembodied head,” which she related to the goddess Coyolxauhqui. Orozco subsequently depicted Huitzilopochtli (interpolated with iconography belonging to the goddess Coatlicue) in El Sacrificio, a fresco panel dated 1937, in the Hospicio Cabañas in Guadaljara. He also made an easel painting titled Culto a Huichilobos, 1949, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City (“Huichilobos” is how the Spanish usually mispronounced Huitzilopochtli), in which he depicted the statue with a bow in its right hand and arrows in its left.